Barbara Bratton’s parents Mom and Dad Elvenia & James Bratton

ㅤ

Barbara Bratton’s Parents Were Politically Aware And Active In Their Community Of Ontario Ca And Surrounding Cities In San Bernardino County.

ㅤ

Fast Track Lending, LLC 200407010240- Was registered on 3/9/2004 by Marc R. Tow in Newport Beach California. 11 months after this date in February 2005 Barbara Bratton was contacted by them. They prided themselves as a ONE STOP SHOP do it all Mortgage Lending Service. When this whole ordeal first started, Barbara Bratton was originally solicited by FTF to refinance her mortgage.

This is a link to a video showing Marc Tow being sentenced in an Ohio court for five years.

Tow, plead guilty to one count of Engaging in a Pattern of Corrupt Activity (RICO), one count of Aggravated Theft and one count of Money Laundering. TAKE OUT THE Age please.

First Franklin Financial was founded in 1981 in San Jose, California, to serve the prime credit market, but in 1994 it switched to serve the nonprime lending market. (One of the co-founders of the company was Bill Dallas, who served as its chairman, CEO and chairman emeritus until 2003, and who subsequently bought OwnIt Mortgage Solutions, which was 20% owned by Merrill Lynch. OwnIt filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy in December 2006.) Barbara Bratton was contacted by FFF.

Select Portfolio Servicing, Inc. (SPS) is a loan servicing company founded in 1989 as Fairbanks Capital Corp. with operations in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Jacksonville, Florida. Barbara Bratton was contacted by them in 2008. SPS’s Motus Operandi is to purchase unsecured leans, then foreclose, then evict under the bank trustee and the alleged trust using highly polluted law firms. The Federal Trade Commission SIGHTED Fairbanks for ILLEGAL SERVICING, which forced them to change its name to Select Portfolio Servicing.

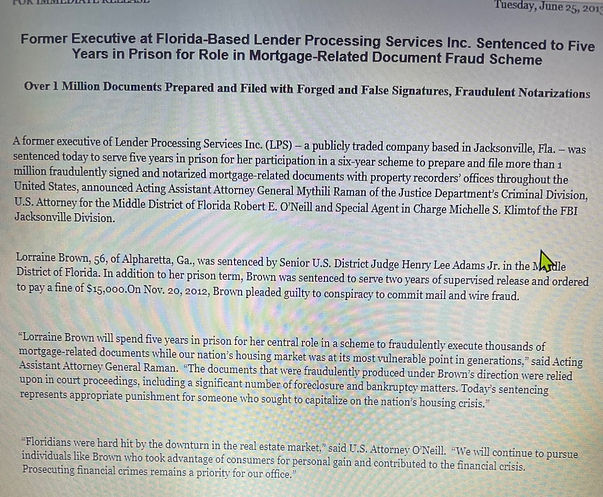

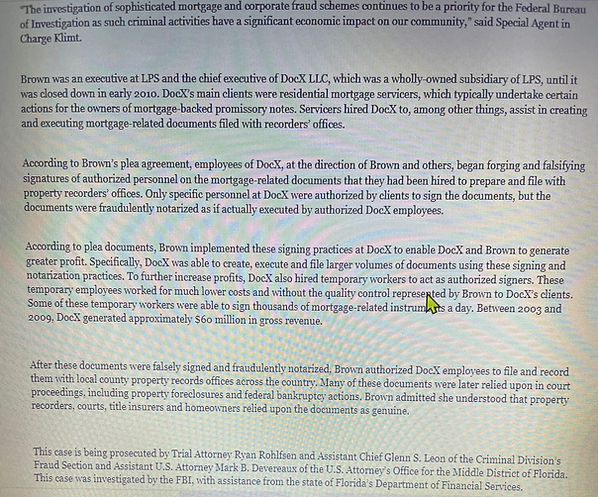

A resident of Georgia, founded DocX LLC (hereinafter, “DocX”) in the 1990s in Ohio. In mid-2005, Jacksonville, Florida based Fidelity National Financial, Inc. (“FNF”) purchased DocX from Brown and her partners. Through corporate reorganizations within FNF, DocX later fell under ownership of Fidelity National Information Services, Inc. (“FNIS”). In mid-2008, FNIS spun off a number of business lines into a new publicly-traded entity, Lender Processing Services, Inc. (“LPS”), based in Jacksonville, Florida. At that time, DocX was rebranded as “LPS Document Solutions, a Division of LPS.” Following this spin-off, Brown was the President and Senior Managing Director of LPS Document Solutions, which constituted DocX’s operations in Alpharetta. At all times relevant to this Information, Brown was the chief executive of the DocX operations.

As you will see later with the documents provided. LPS’s name was all over the fraudulent documents USED TO ILLEGALLY STEAL Barbara Bratton’s HOME.

SHP was incorporated on the 19th of June 2006 (almost 16 years ago) by Charles Karich. On October 29th, 2008 Barbara Bratton’s first contact with SHP’s was when a person from their company was taking pictures of her home. SHP’s FRAUDULENTLY pretends to be retained by US Bank to manage the property when in reality they are retained by Select Portfolio Servicing.

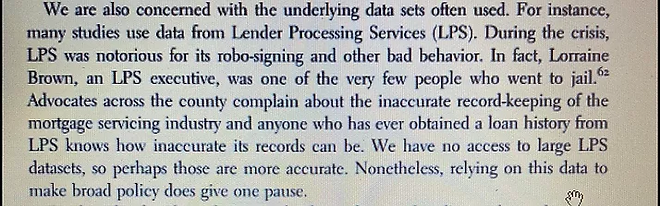

San Bernardino County District Attorney states that Real Estate Fraud Prosecution accounts for activity related to the investigation and prosecution of real estate fraud crimes in the County. Pursuant to Government Code section 27388, the costs related to this activity are funded through a fee charged on recorded documents. On July 22, 2014, the Board of Supervisors (Board) adopted Resolution 2014-164 authorizing an increase of this fee from $3.00 to $10.00. The revenue collected from this fee is transferred to the District Attorney’s Criminal Prosecution unit (less an administrative fee) to offset the cost of staff assigned to investigate/prosecute real estate fraud.

CAL. GOV’T. CODE 27388 4(d) The county board of supervisors shall annually review the effectiveness of the district attorney in deterring, investigating, and prosecuting real estate fraud crimes based upon information provided by the district attorney in an annual report. The district attorney shall submit the annual report to the board on or before September 1 of each year.

CAL. GOV’T. CODE 27388.

(a) (1) States that the fees, after deduction of any actual and necessary administrative costs incurred by the county recorder in carrying out this section, shall be paid quarterly to the county auditor or director of finance, to be placed in the Real Estate Fraud Prosecution Trust Fund.

(c) The county auditor or director of finance shall distribute funds in the Real Estate Fraud Prosecution Trust Fund to eligible law enforcement agencies within the county pursuant to subdivision (b), as determined by a Real Estate Fraud Prosecution Trust Fund Committee composed of the district attorney, the county chief administrative officer, the chief officer responsible for consumer protection within the county, and the chief law enforcement officer of one law enforcement agency receiving funding from the Real Estate Fraud Prosecution Trust Fund, the latter being selected by a majority of the other three members of the committee.

(4) (e) A county shall not expend funds held in that county’s Real Estate Fraud Prosecution Trust Fund until the county’s auditor-controller verifies that the county’s district attorney has submitted an annual report for the county’s most recent full fiscal year pursuant to the requirements of subdivision (d).

Via CAL. GOV’T. CODE 27388 (d) (a), 60 percent of the funds shall be distributed to district attorneys subject to review pursuant to subdivision (d).

Via CAL. GOV’T. CODE 27388 (B) (c) (d), (c). In those counties where the investigation of real estate fraud is done exclusively by the district attorney, after deduction of the actual and necessary administrative costs referred to in subdivision (a), 100 percent of the funds shall be distributed to the district attorney, subject to review pursuant to subdivision (d).

Via CAL. GOV’T. CODE 27388 (4) (d) The county board of supervisors shall annually review the effectiveness of the district attorney in deterring, investigating, and prosecuting real estate fraud crimes based upon information provided by the district attorney in an annual report. The district attorney shall submit the annual report to the board on or before September 1 of each year.

CAL. GOV’T. CODE 27388 (4) (e), A county shall not expend funds held in that county’s Real Estate Fraud Prosecution Trust Fund until the county’s auditor-controller verifies that the county’s district attorney has submitted an annual report for the county’s most recent full fiscal year pursuant to the requirements of subdivision (d).

This email shows the Controller Auditor admitting that the District Attorney Jason Anderson and the office itself have not provided the report for at least five years. This email also raises a big question. If the District Attorney has the data, WHY HAVE THEY NOT BEEN FOLLOWING THE LAW? The D.A has no problem taking the money, but why not reporting about where it goes and how it is used?

The San Bernardino County Sherrif’s role in this is that they are in total compliance with the unlawful detainer courts illegal eviction orders. They use threats of forced entry, conspire with neighbors, and overall terrorize law abiding citizens. They finish the fraudulent conveyance through illegal eviction and lockout. They’re the last piece of the puzzle. Once they get the person out of their home, their equity is stripped and sold to an investor and straw buyers occupy the house without CLEAR TITLE.

“Problems emerging in courts across the nation are varied but all involve documents that must be submitted before foreclosures can proceed legally. Homeowners, lawyers and analysts have been citing such problems for the last few years, but it appears to have reached such intensity recently that banks are beginning to re-examine whether all of the foreclosure papers were prepared properly.”

In some cases, documents have been signed by employees who say they have not verified crucial information like amounts owed by borrowers. Other problems involve questionable legal notarization of documents, in which, for example, the notarizations predate the actual preparation of documents — suggesting that signatures were never actually reviewed by a notary.

On still other important documents, a single official’s name is signed in such radically different ways that some appear to be forgeries. Additional problems have emerged when multiple banks have all argued that they have the right to foreclose on the same property, a result of a murky trail of documentation and ownership.

Other problems occurred when notarizations took place so far from where the documents were signed that it was highly unlikely that the notaries witnessed the signings, as the law requires.

Jerry Brown 2007-2011, Kamala Harris 2011-2017, Xavier Becerra 2017-2021, Rob Bonta 2021- Present.

“In February 2012, with California still reeling from the Great Recession, then-state Attorney General Kamala Harris delivered a bit of good news to Gov. Jerry Brown: The nation’s largest mortgage banks had agreed to pay the state $410 million directly for their role in the subprime mortgage fiasco.”

“While Harris recommended the Legislature spend the settlement on programs to help families victimized by the banks’ illegal lending practices, Brown and the Legislature had other plans. They funneled most of the money to plug holes in the budget and pay down old bond debt that

was strangling California financially.”

Negating the shifty maneuver engineered by one of California’s most experienced politicians (by the signing of SB 861) on Tuesday – after nearly seven years– a state appeals court ordered the state to pull $331 million back from the general fund and use the money to pay for homeowner-assistance programs. “Money was unlawfully diverted from a special fund in contravention of the purposes for which that special fund was established,” Justice Andrea Hoch wrote.

The problem was so bad that, in 2011, when Kamala Harris took over the California Attorney General’s Office, she announced the creation of a statewide task force to tackle mortgage fraud. A big focus of the task force was supposed to be going after scam artists and entities.

And yet three years after the establishment of the Mortgage Fraud Strike Force, Harris’ office has prosecuted only ten cases of foreclosure consultant fraud. Despite the fact that California was the hardest hit state by foreclosure rescue scams, and that it is the home base for more scam artists than any other state, Harris’ strike force has prosecuted fewer foreclosure consultant fraud cases than attorneys general in numerous other states. Moreover, as Harris’ office has failed to act, attorneys general in other states have turned their sights on California, targeting rip-off artists who are based here and have scammed homeowners elsewhere in the country.

obtained by The Intercept alleges that One West BANK rushed delinquent homeowners out of their homes by violating notice and waiting period statutes, illegally backdated key documents, and effectively gamed foreclosure auctions.

ONEWEST BANK, WHICH Donald Trump’s nominee for treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, ran from 2009 to 2015, repeatedly broke California’s foreclosure laws during that period, according to a previously undisclosed 2013 memo from top prosecutors in the state attorney general’s office.

In the memo, the leaders of the state attorney general’s Consumer Law Section said they had “uncovered evidence suggestive of widespread misconduct” in a yearlong investigation. In a detailed 22-page request, they identified over a thousand legal violations in the small subsection of OneWest loans they were able to examine, and they recommended that Attorney General Kamala Harris file a civil enforcement action against the Pasadena-based bank. But Harris’s office, without any explanation, declined to prosecute the case.

Why did her office close the case, deciding not to “conduct a full investigation of a national bank’s misconduct and provide a public accounting of what happened,” as her own investigators had urged? Although we do not know for sure, everything in its totality appears to show that if Harris’s office prosecuted Steve Mnuchin she arguably would not have become the Vice President of the United States.

OneWest Bank has agreed to a more than $7 million settlement over allegations of discriminatory lending that cover the period when Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin was chairman.

Via the law review article above, Prior to subprime lending and mortgage securitization, banks were genuinely concerned about the financial status of their borrowers because the bank itself was incurring a real risk by extending credit. However, this system of having “skin in the game” would soon fade away as banks and financial institutions found innovative ways to unload mortgages and thereby shift the risk in the long term and obtain upfront capital in the short term.

The mortgage lending abuses that led to the housing crisis were born out of a combination of subprime lending and the securitization of mortgages. Both of these together helped form the basis for a system that would ultimately speed toward a crashing and disastrous end.

Beginning in or around the early 1990s, individuals who lacked the ability to qualify for credit under customary underwriting standards were nevertheless granted mortgage loans by banks across the country. These subprime borrowers—who almost always failed to understand the nature of the documents they were signing or the obligations they were incurring—were enticed to enter into these credit agreements by promises of low interest rates on the front end, which would only adjust to a higher rate a few years into the term of the loan- This is exactly what happened to Barbara Bratton!

Although these borrowers lacked the ability to make their mortgage payments once the interest rates spiked, they often thought they would be able to refinance their debt for another low interest rate before that time would arrive. Under these auspices, subprime mortgage lending flourished such that “subprime mortgages grew from five percent to over twenty percent of all new mortgages” between the years 1994 to 2004.

The securitization process involved a labyrinthine scheme of buying, selling, swapping, and insuring intricate—and almost always poorly conceived—legal instruments that comprised a host of mortgage/credit rights through various nominees of the true parties. This system started with the lending institution that initially made the loan to the borrower. This could be either a Banking institution or a mortgage broker, in either case, this party was called the MORTGAGE ORIGINATOR.

The originator would, nominally at least, review the credit history, employment status, and other financial indicators of the borrower and assess whether the prospective borrower had the ability to repay the loan. It was at this stage of the transaction that subprime borrowers— those who, by all accounts, could not repay the loan—were nevertheless approved for credit. The borrower would receive the purchase funds in the form of loan proceeds and would contemporaneously sign a promissory note and a mortgage on the property.

Next, almost immediately, the mortgage originator would sell the mortgage and the note to a third party called an issuer or an arranger. These arrangers would purchase hundreds and thousands of mortgages and notes from various mortgage originators from across the country and, by combining them together, created a form of security (like stock or a bond) that could then be bought, sold, or traded on the open market to third party investors, typically through buying a nominal interest in a trust that would have ownership of the mortgage pool A.K.A (GREED).

From this point, although nothing had changed in terms of the borrower’s position, the mortgage payments no longer were directed at the originator. Rather, the third-party investors who purchased interests in the securitized pool of mortgages rely upon yet another third party—a mortgage-servicing agent—to handle the monthly collection of note payments and to otherwise deal directly with the borrower.

Naturally, the ability of mortgage lenders to off-load their risk to third parties almost immediately upon making the risky loan removed a major protection for borrowers. Under historical lending practices the bank assumed the risk that a default might occur if the borrower was unable to pay. Due to this risk, banks were very concerned about the credit worthiness of their borrowers, since a failure to adequately assess a borrower’s financial position could result in a direct hit to the bank.

With the ability to sell the loan immediately after making it, this borrower protection, originally built into the system of lending, was completely eviscerated. A bank need not worry about the quality of the borrower since a subsequent default would be someone else’s problem.

This was especially true since in the early years of adjustable rate subprime loans the borrower was indeed able to make the monthly payments. It would not be until about two to three years into the loan, when the originator bank had long since sold the loan to a third party, that the rate would adjust and become too high for the borrower to make the debt service. And to add yet another defective wheel to the cart, the mortgage servicer who was charged with dealing with the borrower—including addressing any issues that may arise if the borrower became behind on his payments—was financially incentivized by virtue of the servicing agreement to work in favor of neither the interest of the borrower nor the owner of the loan.

This defective system, underpinned by greed and buttressed by artificial home prices, finally came crashing down beginning in 2006. As property values decreased, subprime borrowers, who up until now believed they could refinance their debt before the adjustable interest rates spiked, found themselves unable to do so. Because they could not continue to enjoy their relatively low monthly payments, and because they could not sustain these now adjusted and much higher debt obligations, they defaulted en masse. In turn, banks—or, rather, their mortgage servicers—began to foreclose on these defaulted properties across the United States. However, because these properties were underwater—meaning that the mortgage debt encumbering these properties was far in excess of the actual value of the property that it secured—foreclosure sales failed to bring in an amount sufficient for the banks to recover their loss.

As a result, banks were forced to purchase the mortgaged property themselves, which thereby created a situation where lending institutions became the owners of a massive number of foreclosed properties—a role for which they were entirely unfit and unprepared.

Since borrowers were no longer making payments under their loans, the market for the many mortgage-backed securities that were now in the hands of various financial institutions, pension funds, and other investors came crashing down. In essence, these mortgage-backed securities that had come to permeate the entire United States economy and reach into every sector became almost valueless.

As the massive wave of defaults swept across the country, lenders were forced to initiate foreclosure proceedings quickly in an attempt to rehabilitate the defaulted properties and sell them to third party purchasers, thereby recouping their losses.

Mortgage lenders were attempting to create a sort of nation-wide system of real estate transfers through the mortgage securitization system

In this way, interests in property (mortgage interest, to be exact) were sold, bought, and traded far and wide across different markets through a fairly informal system. However, property law—including the law of mortgages—is governed primarily by state law, which varies depending on the jurisdiction. This extends, in turn, to the ways in which mortgagees can foreclosure on property. Although foreclosures can occur either through a judicial or extrajudicial process—the availability of which depends upon the jurisdiction—each type of process involves a strict adherence to state law procedural steps and necessary borrower safeguards to ensure that there is no overreaching by the creditor.

Since the process of foreclosing on property is so elaborate and requires the observance of so many requirements, foreclosing lenders are charged with conducting a great deal of due diligence and exercising great prudence before initiating such proceedings against a defaulting borrower. “These procedures reflect the need to assure that ownership rights in property are neither extinguished nor created in an environment with inadequate legal circumscriptions.”

As a general matter, the foreclosing party must ensure that (1) they have the legal authority to enforce the mortgage, that they (2) have the correct description of the mortgaged property, (3) that the actions of the borrower validly constitute a default and therefore trigger a right to foreclose, (4) and that the proper parties who are entitled to notice of the foreclosure according to state law and constitutional due process considerations are served. Any defect in the process or failure to follow the necessary procedural steps can result in an illegal foreclosure.

In the wake of the housing crisis, as more and more properties came up for foreclosure, lenders and their mortgage servicers began to realize that, by virtue of the overly informal—and some say haphazard— documentation of the transfer of mortgages from one party to another over the course of time that many of the essential documents required to foreclosure, such as the original promissory note, were unable to be found.

Then a host of additional issues arose over whether the mortgage servicer had the right to foreclose on the property at all if the nominee listed on the mortgage was MERS, a privately-run clearing house which operated in lieu of proper assignments of the promissory notes secured by the mortgages. Mers stands for Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems. There were broken chains in the transfers of the mortgage from one investor to the next, therefore cutting off the ability to show a clean chain of title to the promissory note all the way back to the original lender. Additional questions arose as to whether, although the note continued to be transferred nominally through the MERS system, the note and the mortgage had been impermissibly separated from one another, thereby causing the holder of only the security right (the mortgage) to lack the ability to enforce the device due to its failure to also hold the principal obligation (the note).

Lenders and their mortgage servicers began to realize that the system they had created produced a framework of defects and broken parts that would ultimately render them unable to foreclose through the traditional legal process.

In order to accommodate this DEFECTIVE SYSTEM and thereby still allow lenders to foreclose on their mortgage, courts began allowing the submission of AFFIDAVITS whereby the foreclosing party would swear to the court, under oath, that it was indeed the legal title holder of the promissory note and had the full authority to foreclose on the property.

This abbreviated procedure was dependent upon the assumption that the foreclosing party had conducted the necessary due diligence to ensure that the information to which they were swearing in the affidavit was indeed correct. This would involve going through various documents, assignments, MERS records, and records contained in the various state recording systems to ensure that title to the debt could be validated.

Banks faced with so many foreclosures and hemorrhaging money from their immense losses would often hire only a few individuals to investigate the foreclosure records and sign the affidavits. Quickly these individuals would begin signing the affidavits without conducting any due diligence at all—asserting the lender’s right to the promissory note without the slightest clue as to whether this could be substantiated. This practice became known as “robosigning” since the bank official would sign the affidavits, almost as a mere matter of course, with relatively little concern as to their authenticity. Oftentimes a bank would “employ only one person to sign up to 10,000 foreclosure affidavits per month.

Before 1995, typically a qualified home buyer applied for a mortgage loan (whole-loan) with his/her local bank, credit union or savings and loan. The credit-worthy borrower agreed to make payments until the mortgage debt was paid in full. Around 1995, a new breed of loan came into play—the sub-prime loan. These loans (often times for one hundred percent or more of the market value of the residential property and no longer dependent upon a borrower’s credit worthiness) changed the landscape of mortgage banking, leading, in part, to the current foreclosure crisis.

Knowing that their borrowers were not credit worthy and that the borrowers’ home mortgages would almost certainly end in default, mortgage lenders unloaded these loans as quickly as possible to large institutional banks. These banks, in turn, bought and sold the loans amongst themselves and subsequently pooled them into trusts and then converted them into mortgage backed securities (also referred to as collateralized debt obligations (“CDOs”), meaning that the asset behind the paper is real property). These CDOs were bought and sold by and to investors. Mortgage-backed securities were almost uniformly rated AAA or Aaa by Fitch, Moody’s and Standard & Poors. The AAA rating was appealing to risk adverse investors and these mortgage backed securities ended up in conservative pension funds such as CalPERS and conservative investment brokerage funds owned by companies such as MetLife, Blackrock, Inc. and Allstate.

In the midst of creating these trusts and mortgage-backed securities, MERS was created to shuffle these loans quickly between lenders, leaving homeowners unable to find out who actually owned their mortgage at any given time.

After the financial collapse of 2008, MERS began foreclosure actions on behalf of lenders. The creation of MERS allowed mortgage companies to list MERS as the proxy for the true mortgage holder in local government records and to record subsequent changes of ownership in the MERS system only.

A spokeswoman for Fannie Mae told the New York Times that Fannie Mae could never rely on MERS to find ownership of a loan. In 2010, Alan M. White (Law Professor at Valparaiso University Law School, Indiana) matched MERS ownership records against those in the public domain and found that fewer than thirty percent of the mortgages had accurate records in MERS. Robo-signed documents, inaccurate or non-existent record keeping, the failure to publicly record assignments of mortgages and the use of MERS as the mortgagee or nominee have led to the homeowners’ inability to figure out who owns and services their mortgages or to trace back their chain of title. In using the inaccurate and alleged to be fraudulent MERS system, banks are actually denying homeowners their DUE PROCESS RIGHTS before they lose their homes to foreclosure.

Furthermore, because the MERS system allowed lenders to avoid the time and expense of going through the County Recorder’s office to file and record title documents, MERS also robs County Recorders of filing fees. In fact, various county recorders have begun to take action attempting to recoup some of these fees.

Homeowners are arguing that MERS does not have a right to initiate foreclosure actions because MERS does not hold the title and the corresponding note to their properties. These same homeowners are also arguing that the MERS system does not accurately show which lender holds the trust deed for title on the foreclosed property. Furthermore, even if MERS forecloses a property for a lender (that does not actually have title and the corresponding note to the property), an argument could be made that the lender may be prohibited from reselling the property because the lender cannot sell that which it does not own. According to (past)court rulings, there may be no standing to foreclose without proof of title and the note, there may be no standing to foreclose. See U.S. Bank National Ass’n v. Ibanez, 941 N.E.2d 40, 44 (Mass. 2011); In re Agard, 444 B.R. 231, 254 (Bankr. E.D.N.Y. 2011).

MERS has acknowledged, and recent cases have held, that MERS is a mere nominee—an entity appointed by the true owner simply for the purpose of holding property in order to facilitate transactions. Recent court opinions stress that this defect is not just a procedural one but is also a substantive failure, one that is fatal to the plaintiff’s ability to foreclose. MERS was set up without considering how it would destroy or seriously dilute accurate and recorded chain of title records in event of mass foreclosure. Already, chains of title have been lost in the frenzy of trading and packaging these mortgages into mortgage-backed securities. Today, MERS servicers and related foreclosure mills are literally breaking a centuries-old custom that protected property rights by requiring every sale of property to be publicly recorded (pursuant to race/notice statutes) and requiring that any creditor claiming a right to foreclose demonstrate clear title (with an endorsed note in the creditor’s name and a record at the county office showing transfer of the property).